Image courtesy of Stuart Miles at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Dave Ramsey hands out advice to millions of people every day, and much of the time he’s right on track – or at least relatively so. However, like all purveyors of financial advice to the masses, his advice should be taken with a grain of salt.

There are two reasons for this: First, your circumstances are very likely to be very different from the individual to whom the “vending machine” advice is rendered. A subtle change to the circumstances can make a major difference as to whether the recommendation applies to you the same as the asker. Dig deeper than just taking the recommendation verbatim, making a decision based on your own circumstances.

Second, the very nature of the forum that Dave (and Suze, Malcom, and others) use, that of mass-produced financial advice, is oriented toward the sound bite. Take the recommendation Dave makes in this recent column as an example. In the first question, Dave’s got no idea what the tax situation is for Jennifer, her income, her age (several years before retirement could be 5 or 50!), if she has other accounts, not even if she’s married. Yet his response is unequivocal: a Roth 401(k) is best – presumably (at least in part) because that’s what Dave has chosen for himself. Dave’s financial circumstances are bound to be drastically different from Jennifer’s, but the sound bite wins out. Millions of followers now have the idea that in all circumstances, if you have a Roth 401(k) available, you should utilize it. That’s not exactly poor advice, but it’s very generalized and incomplete at the very least.

A proper answer would require more information about Jennifer, much more. For example, if it turns out that Jennifer has a very high income now and expected future income will be much lower, the traditional 401(k) could be the best for her.

Another problem with this answer is Dave’s calculation of the tax hit on distribution. He says it could be $300k to $400k on a million-dollar account. That could be the case if Jennifer withdrew the entire $1 million in one tax year (makes for a great sound bite!). However, if she takes that money out over a 20-year timeframe at $50,000 per year, is married, and that’s the only income that Jennifer and Mr. Jennifer receive, at today’s tax rates they’d pay less than $64,000 in tax during that period. Not such a juicy sound bite, but likely a lot closer to reality.

My point is not that you should disregard what Dave Ramsey (or any of the other financial “gurus” out there) has to say. Much of the time, as I stated before, he gives good guidance (notwithstanding his irrational fear of debt and his expectation of a 12% return from the stock market). I like a lot of what he has to say, helping folks via his Financial Peace University and whatnot. Plus, how can you not like a guy whose offices are right next door to a Cracker Barrel and a Krispy Kreme, all right across the street from a swanky Galleria Mall??? No, my point is to understand the nature of the recommendations given, and that your circumstances are most likely very different from the seeker of wisdom from the mount.

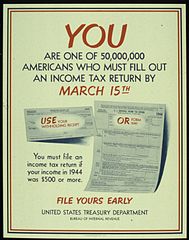

When filing your tax return you want to make sure that you don’t make mistakes. Mistakes can be costly in terms of additional tax and penalties, as well as the extra time and grief they can cause you. Most of the time using e-filing software can help you to avoid these mistakes, but you should check over the return anyhow to make certain you haven’t fat-fingered something or if something didn’t go wrong with the software.

When filing your tax return you want to make sure that you don’t make mistakes. Mistakes can be costly in terms of additional tax and penalties, as well as the extra time and grief they can cause you. Most of the time using e-filing software can help you to avoid these mistakes, but you should check over the return anyhow to make certain you haven’t fat-fingered something or if something didn’t go wrong with the software.

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.