Photo credit: jb

We usually do a good job of determining who is to be the Primary Beneficiary or Beneficiaries of our retirement accounts – this is often our Spouse or some significant other such as a child (although others may be designated, more on that below). However, the contingent beneficiary designation is, in my experience, left wide open much of the time.

The idea is that your Spouse as the Primary Beneficiary would take ownership of the account, and then designate a new Primary Beneficiary. This way your spouse will get the benefit of the account and he or she can choose whomever he or she wishes to be the Primary Beneficiary(s) of the account – possibly a new spouse, or the couple’s children, or even a favorite charity.

But what happens if the Spouse predeceases the account owner, or they die simultaneously? Without a contingent beneficiary designation, the estate will determine how the account will be distributed, and this can cause some problems if there is no will specifically naming beneficiaries for such situations. For one thing, without specific beneficiaries named, it is likely that the entire account would have to be distributed within 5 years – rather than allowing for a stretch distribution, or even the 10-year default distribution for named beneficiaries.

Naming a contingent beneficiary (or class of beneficiaries) can help to resolve this situation. For example, you could name your children specifically as contingent beneficiaries and define the percentage each child should receive. Another way to do this would be to name the class – “All my children” – as contingent beneficiaries. This way all the children would share equally. (This could also be a way to name a Primary Beneficiary class as well.)

Image via Wikipedia

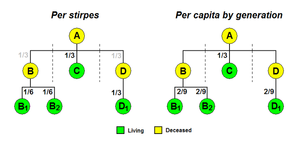

But what if one of your children pre-deceases you when you’ve named the class of beneficiaries? How do you want that situation to be handled: to have the remainder of your children split the benefit equally, or for the deceased child’s heirs to receive that child’s share? In order to do this, you need to specifically denote that the beneficiary is “All my children, per stirpes”. This phrase will cause the account to be divided equally among your children, living or dead, with the share for each deceased child going to his or her children.

The alternative to per stirpes is to distribute to a class of beneficiaries “per capita”, and this could be by generation or by number of beneficiaries. See the chart to have a better explanation of per capita versus per stirpes.

Multiple Primary Beneficiaries

If you have designated a class of beneficiaries (as described above) as your Primary Beneficiary – you may have other plans that you’d like to have enacted in the event of one or more of the class pre-deceasing you.

Instead of your spouse or your children, what if you’re not married and have no children? In this case, you might wish to leave a portion of your account to your sibling(s), and perhaps a portion of the account to a charity.

For a complex example, let’s say you have a favorite charity that you wish to designate to receive 1/2 of your IRA at your passing, and the other half you’d like to go to your brother. In the event that your brother should happen to pass away before your own demise, unless you’ve designated a contingent beneficiary, his estate will receive the half designated to him.

But what if you really wanted it all to go to the charity in the event your brother pre-deceased you? Properly designating the charity as the contingent beneficiary in the event of the brother’s early death would take care of this.

Disclaiming, Too

One more thing: in designating your contingent beneficiaries, you should also make provision for the contingent(s) to take claim in the event that the Primary Beneficiary disclaims the inheritance. In this case, the Primary could determine that he or she prefers to have the account in the hands of the contingent(s), and so disclaims the inherited account.

Without specifically addressing this in your beneficiary designation, your estate could become the beneficiary of the account, which may or may not carry out the wishes of the disclaimer. This is especially important for ERISA-controlled plans (401(k) or 403(b), for example) due to the rules ERISA has for distribution.

You may need to work closely with your custodian to properly make this contingent beneficiary designation, as the forms they give you are purposely simple. And sometimes the custodian will refuse to give you the option of drafting your own letter of instruction for beneficiary designation. In that case, the only way you can get your designation corrected would be to change custodians – and this might be a problem if it’s an employer-sponsored plan.

Just keep this in mind as you consider your beneficiary designations – but do what you can to make sure that your wishes are going to be carried out the way you hoped.

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.