There has been a debate going on in the financial advisory world for many years. You see, there are two primary governing bodies for folks in the financial services business: the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), which promotes a fiduciary standard, and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), promoting a suitability standard. These are the two primary governing bodies (but there are others).

There has been a debate going on in the financial advisory world for many years. You see, there are two primary governing bodies for folks in the financial services business: the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), which promotes a fiduciary standard, and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), promoting a suitability standard. These are the two primary governing bodies (but there are others).

The Players

The SEC, an arm of the US federal government, has regulatory authority over Registered Investment Advisors (RIA) and Investment Advisor Representatives (IAR) who provide investment advice pursuant to the Investment Advisors Act of 1940 (the ’40 Act). These folks are advice-givers first and foremost, and are held to a fiduciary standard.

FINRA, on the other hand, is a Self-Regulatory Organization (SRO) which regulates Registered Representatives of brokerage companies, among others. The people in this group are brokers, sellers of products first and foremost. Members of FINRA are held to a suitability standard.

The SEC was created in 1934 with the passage of the Securities Exchange Act (the ’34 Act) created in 1934 and FINRA’s predecessor, the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), was created in 1939 due to some amendments made to the ’34 Act. The prime reason I’m giving you this history is to show you just how long the tail can be for legislation passed during times of national economic crisis – these organizations have been operating for 70 and 75 years following their creation in response to situations that developed prior to the (and some believe had direct cause for) the Great Depression. Legislation that is being considered today could have similar monumental impact.

But enough history for now – there are literally tons of nuances to consider throughout the history of these two organizations, but the question at hand is the standard to which folks in the financial services sector are held.

Definitions

Fiduciary Standard – A fiduciary is someone who has undertaken to act for and on behalf of another in a particular matter in circumstances which give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence. A fiduciary duty is the highest standard of care at either equity or law. A fiduciary is expected to be extremely loyal to the person to whom he owes the duty (the “principal”): he must not put his personal interests before the duty, and must not profit from his position as a fiduciary, unless the principal consents. Further, he must disclose any conflicts of interest, including potential conflicts of interest. The word itself comes originally from the Latin fides, meaning faith, and fiducia, trust. (from Wikipedia)

Suitability Standard – brokers are required to: 1) know their clients’ financial situations well enough to understand their financial needs, and 2) recommend investments that are suitable for them based on that knowledge. Brokers are not required to provide upfront disclosures of the type provided by investment advisers, including, but not limited to their conflicts of interest.

The Debate

Financial planners, financial advisors, etc. (for there are many names by which advisors call themselves) are not per se regulated by one standard or another, but rather it depends upon the situation. Certified Financial Planner™ practicioners (CFP®) are held to a fiduciary standard by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, while most other credentials do not carry such a standard requirement.

It is apparent that the suitability standard is a portion of the fiduciary standard: if a person is operating as a fiduciary, putting the client’s interests first, then investments recommended are by definition suitable to the client’s situation. The industry recognizes that there is a lot of confusion in the way things are presently laid out, and are working toward a single standard for both types of advisors.

Folks presently held to the suitability standard argue that the fiduciary (often referring to this as the “f-word”) standard is aspirational in nature, where the suitability standard is very clear and direct. On the other side of the spectrum, those held to the fiduciary standard believe that the inclusion of the FINRA brokers in this standard would serve to dilute the standard – that there would be “degrees” of fiduciary standard to which some folks would be held, while still claiming the mantle.

This is particularly newsworthy as recently the head of FINRA indicated that he thought there should be a single standard, and that he thought the fiduciary standard was the appropriate direction.

The Real Question

The burning question in my mind is this: from the consumer point of view, do you care? Did you even know about these two standards in the first place? Did you know that when you go to a brokerage and ask for advice, that the primary standard to which the advisor is held is to ensure that whatever they have for sale is in some way suitable to your situation even if it’s not necessarily in your best interest? For example, it is entirely possible for a broker to consider a high-cost annuity suitable to your situation, even though it’s not necessarily in your best interest.

This debate means a lot to folks in this industry, and I think it’s pretty clear what you’d probably like, but I just wondered if you care enough to comment on it.

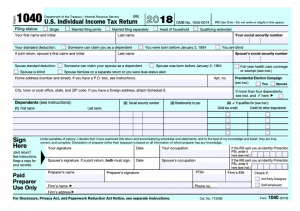

For 2019, there is a change to the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA) for Medicare. The change is to add another level of adjustment to IRMAA for 2019.

For 2019, there is a change to the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts (IRMAA) for Medicare. The change is to add another level of adjustment to IRMAA for 2019.

In this installment of our ongoing Principles of Pollex series, we’re going to talk about two Rules from the financial world that are actually real, true, undisputed Rules, rather than the guidelines with dubious proof that we’ve talked about before. These two Rules are not open to interpretation. The first is about investments, and the second is about loans. Both are useful in their own ways…

In this installment of our ongoing Principles of Pollex series, we’re going to talk about two Rules from the financial world that are actually real, true, undisputed Rules, rather than the guidelines with dubious proof that we’ve talked about before. These two Rules are not open to interpretation. The first is about investments, and the second is about loans. Both are useful in their own ways… As of 2018, it is no longer possible to deduct IRA losses from your income. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 eliminated this and many other miscellaneous itemized deductions.

As of 2018, it is no longer possible to deduct IRA losses from your income. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 eliminated this and many other miscellaneous itemized deductions. In today’s society, the historically “traditional” family is becoming less and less commonplace – apparently as many as 50% of all children under age 13 are currently living with one biological parent and that parent’s current partner who is not a biological parent of the child. Often as well, there is a significant age differential between the biological parent and the parent’s partner. Even if there is little difference in ages, quite often situations arise where estate planning including IRAs can become complicated.

In today’s society, the historically “traditional” family is becoming less and less commonplace – apparently as many as 50% of all children under age 13 are currently living with one biological parent and that parent’s current partner who is not a biological parent of the child. Often as well, there is a significant age differential between the biological parent and the parent’s partner. Even if there is little difference in ages, quite often situations arise where estate planning including IRAs can become complicated.

Even with our best laid plans, sometimes we make mistakes. Perhaps you underestimated your income for the year and contributed more to your IRA than could be deductible; maybe you rolled over an amount that was not eligible for rollover; or maybe you made a contribution to an IRA that you were not eligible to contribute to, such as an inherited IRA. Whatever the case, you have an over-contribution into an IRA and need to take action, otherwise you can be setting yourself up for some penalties and other un-wanted taxation.

Even with our best laid plans, sometimes we make mistakes. Perhaps you underestimated your income for the year and contributed more to your IRA than could be deductible; maybe you rolled over an amount that was not eligible for rollover; or maybe you made a contribution to an IRA that you were not eligible to contribute to, such as an inherited IRA. Whatever the case, you have an over-contribution into an IRA and need to take action, otherwise you can be setting yourself up for some penalties and other un-wanted taxation. This question comes up pretty regularly – and recently it came up again via Twitter from a reader. I’ll give this my best explanation – but you have to grant me a favor: Please understand that in my explanation I am not defending the practice, I am simply explaining why Social Security benefits are included as taxable income.

This question comes up pretty regularly – and recently it came up again via Twitter from a reader. I’ll give this my best explanation – but you have to grant me a favor: Please understand that in my explanation I am not defending the practice, I am simply explaining why Social Security benefits are included as taxable income.

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.