Photo credit: jb

In case you didn’t realize it, the IRS made some changes to the RMD process, which applies to Required Minimum Distributions in 2022 and years thereafter. For most folks this is a minor adjustment which actually reduces your RMD a bit. But for folks with inherited IRAs that aren’t subject to the 10-year payout or the 5-year payout, you’ll want to pay attention to the section below about RMDs for Inherited IRAs.

So what changed? The actuaries at the IRS (under an executive order from the President) reviewed the then-current tables in 2018 and determined that the changes in longevity made the old tables inaccurate. So new tables were generated, and they are applicable beginning with tax year 2022.

These tables – specifically Table I (the Single Life Expectancy table – used for inherited IRAs), Table II (Joint and Survivor table – for use when there is more than 10 years between the ages of a couple), and Table III (Uniform Life Expectancy table – for regular IRAs when there is less than 10 years between the ages of a couple, or the individual is single) – were updated for 2022 to reflect longer lifespans for Americans that are subject to these required distributions.

Generally the Uniform Life Table (Table III) is the most commonly used table. If you’re using this table for RMDs from your IRA (or other qualified plan), you will just refer to the new table (use the link above) when you calculate the RMD for 2022. It’s really that simple, and you may notice that using the new table results in a slightly smaller percentage of your account as an RMD. This is because the table was lengthened, making the earlier payments a bit smaller.

The same is true if you have a regular IRA and you’re using Table II, for a situation where your spouse is more than 10 years younger. Again, just apply the new table factor and you’re good to go, with a slightly decreased RMD percentage for 2022 and beyond.

RMDs for Inherited IRAs

Beginning with 2022, if you inherited an IRA prior to the rule changes which took effect in 2020, you were likely using Table I, the Single Life Expectancy table. If you inherited an IRA in 2020 or later, unless you’re a Eligible Designated Beneficiary (EDB), you’ll be subject to the 10-year payout period. This means that you don’t have to take annual distributions from the inherited IRA, you just need to completely distribute the IRA by the end of year of the 11th anniversary of the death of the original owner (it’s called the 10-year payout period because you have a full 10 years to withdraw). In some cases you might be subjected to a 5-year payout period, but that’s a topic for another time.

If you just inherited this account in 2021, the RMD for 2022 (your first year of RMDs) is straightforward. Look up your current age on Table I, the Single Life Expectancy table, and divide your 2021 year-end balance by the factor given. Then in each subsequent year, subtract 1 from the factor you got for the prior year, and divide your previous year-end balance by the new figure to produce your RMD.

However, if you inherited the IRA sometime prior to 2021 and had begun taking RMDs in 2021 or earlier based on the old tables, you have to make an adjustment to your process. Essentially you need to go back to when you first calculated an RMD for yourself on this account, and replace that figure with the new figure from the updated Single Life Expectancy table. Now, you’ll subtract 1 from the new factor for each year that has passed since you started. This will bring you to the new RMD factor for 2022. For each subsequent year, you’ll just subtract 1 from last year’s factor and divide.

Let’s walk through an example which may help your understanding:

Michelle inherited an IRA from her father, who died in 2018. Michelle was required to begin taking RMDs from the account in 2019 when she was 52 years old. The account’s year-end balance for 2018 was $90,000. From the old Single Life table, Michelle’s age 52 gave her a factor of 32.3. Dividing the year-end balance by 32.3 results in $2,786.38, which is Michelle’s Required Minimum Distribution for 2019.

For 2020, no RMDs were required (waived by the CARES Act), so Michelle skipped this distribution. If the “skip” wasn’t in place, Michelle would have taken the 2019 year-end balance in the IRA ($92,446) and divided it by her updated factor of 31.3 (subtracting 1 from her original factor). This would have resulted in an RMD of $2,953.55 for 2020.

For 2021, RMDs were once again required. Michelle took the year-end balance from the IRA ($97,992) and divided it by the updated factor of 30.3 (again, subtracting 1 from last year’s factor). The resulting RMD is $3,234.06.

The 2021 year-end balance of the IRA has grown to $103,286. If the old table was still in effect, all Michelle would have to do is subtract 1 from last year’s factor, resulting in 29.3, and divide the balance by that number. The result would have been an RMD of $3,525.12.

However. There’s a new table in town.

The implementation of the new table requires Michelle to go back and do some adjusting. She needs to go to the new Single Life Expectancy table and get her new factor from when she started RMDs – her age 52. This new factor is 34.3. Since 2022 is the third year since she started RMDs, she’ll subtract 3 from her factor, to come up with the new factor of 31.3. Dividing the 2021 year-end balance of $103,286 by 31.3 results in an RMD of $3,299.87 – a few hundred less than the original table’s result.

Then for next year, Michelle will subtract 1 from her 2022 factor, which results in 30.3. She’ll divide the 2022 year-end balance in the IRA by that factor to calculate her 2023 RMD.

In all cases that I can think of, these new tables will result in a lower RMD for everyone. The good news is that if you don’t make the adjustment, the only thing that will happen is you will take a slightly higher RMD than you had to. This will result in a slightly shorter payout period for your IRA – not the end of the world, but if you’re hoping to stretch that IRA out as long as possible, you’ll want to use the new tables.

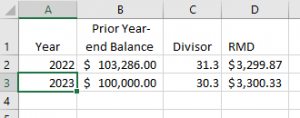

A sample spreadsheet to calculate RMDs

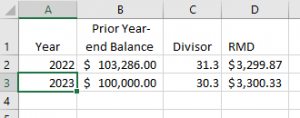

Here’s a way you can use a simple spreadsheet to calculate the figures:

In a blank spreadsheet (Excel or GSheets or whatever spreadsheet tool you use), list the year in the first column. Second column will have your year-end balance from the prior year. The third column will hold your Table I factor. And in the fourth column, you can calculate the resulting RMD. I use the simple formula of “=B2/C2” (don’t include the quotation marks) in the fourth column (column D).

It looks like this when finished:

Then for the next year you can put the formula “=C2-1” (don’t include the quotation marks) in your third column (cell C3), which will subtract 1 from the prior year’s factor. In my sample I just made up a number for the 2022 year-end balance (which is in cell B3) to make the calculation in D3 work.

For subsequent years, fill in column A with the applicable year, column B with the new year-end balance, and then copy down the formulas in columns C and D. You can do this quickly by highlighting the current year’s C column, then while holding down the shift key hit the right arrow and the down arrow once each – this expands your highlight to current cells C and D and the corresponding C & D below. Release the shift key, and then hit Ctrl+D on your keyboard. Sorry Mac users, I don’t have your shortcut but I’m sure it’s just as simple.

I have covered the topic of

I have covered the topic of  Remember when we talked about how your

Remember when we talked about how your  If you’ve ever read up on Social Security retirement benefits, you’ve likely come across a number called the Primary Insurance Amount, or PIA. So just what is PIA? That is, besides the airport designation for the General Wayne A. Downing, Peoria (IL) International Airport?

If you’ve ever read up on Social Security retirement benefits, you’ve likely come across a number called the Primary Insurance Amount, or PIA. So just what is PIA? That is, besides the airport designation for the General Wayne A. Downing, Peoria (IL) International Airport?

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.