Now that we have a few months’ worth of the new tax tables (from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017) under our belts, it’s a good idea to do a withholding checkup against your paycheck. A withholding checkup is a common exercise that many people perform to make sure that they are having enough, but not too much, tax withheld throughout the year. You can do a withholding checkup at any point in the year (after at least one paycheck), so feel free to use this process later in the year as you see fit.

Now that we have a few months’ worth of the new tax tables (from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017) under our belts, it’s a good idea to do a withholding checkup against your paycheck. A withholding checkup is a common exercise that many people perform to make sure that they are having enough, but not too much, tax withheld throughout the year. You can do a withholding checkup at any point in the year (after at least one paycheck), so feel free to use this process later in the year as you see fit.

Note to retirees: this withholding checkup will not work correctly for you. You will need to review the Mid-year Estimated Payments Checkup to make sure you have the proper amount of tax being withheld from your various sources, and whether or not it is necessary for you to make estimated payments throughout the year.

The good news is that the IRS has a calculator available that can help you do the withholding checkup. If you go to the IRS’ website (www.IRS.gov) and search for “tax withholding”, you will be able to access the Withholding Calculator – or just click the link to go to the Withholding Calculator page directly. Have your most recent pay-stub available when you go to the calculator.

Mid-year withholding checkup

As you work through the calculator, you’ll need to know a few things about your tax return, so it will be handy to have a copy of your 2017 return available (or at least know the answer to the questions below):

- Filing status

- Can anyone else claim you as a dependent? Same for your spouse if filing jointly.

- How many jobs have you worked (or will you work) in 2018? Same for your spouse.

- Do you have a 401k, cafeteria plan (such as healthcare or child-care) through your employer? Same for spouse.

- Will you or your spouse receive a taxable scholarship or grant in 2018?

- Are you or your spouse age 65 or older in 2018? Blind?

- Number of dependents (not including spouse) to claim on your 2018 return.

- Number of children that will be claimed for child-care expenses, child tax credit, and earned income credit

You’ll also need the specific information from your pay-stub: gross income, bonuses, deferred income (to a retirement plan), how much is being withheld for income tax (be careful and only count the income tax, not Social Security or Medicare tax, or FICA), and how many pay periods are remaining. For all of this information, you will need the current pay period amount and the total year-to-date amount, as well as how often you are paid, with how many pay periods are remaining. You’ll need to gather this information for each job that you hold or intend to hold through the year.

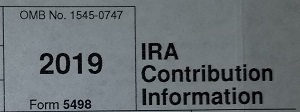

Next, you’ll add in any non-wage income – such as rental income, interest and dividends, or partnerships and corporation income. You’ll also estimate any reductions to income that you may have, such as deductible contributions to an IRA. If you’re not sure about these numbers (and who could be, this early in the year?) then just use the figures from your 2017 tax return.

After that, you’ll need to estimate your deductions. If you’ve always used the standard deduction in the past, chances are you’ll continue to use the standard deduction in 2018. If you have had circumstances change, such as buying a house, moving to a higher-tax state, you’ve made significant contributions to charity, or you have significant medical expenses (beyond insurance coverage), then you’ll want to go through the exercise of calculating your itemized deductions. The calculator steps you through the process of estimating your taxes, medical expenses, interest paid on mortgages, charitable contributions and other itemized deductions.

The result will show you how you should make changes (if needed) to your W-4 with each employer. If you make these changes, your withholding should be adjusted to fit your income tax needs for the current year.

It is critical that, if you make changes to your W-4 as a result of this withholding checkup, you should come back and re-check again early in the following year to make sure everything is set up correctly for the coming year.

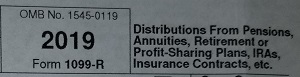

If you are retiring before the “normal” retirement age of 59½ or older, or if you find yourself in need of money, you may need to make an early withdrawal from your retirement plan. An early withdrawal from your retirement plan is not without consequences – there will be taxes for sure, and quite possibly (likely?) penalties (referred to as “additional tax on early withdrawals” below). For

If you are retiring before the “normal” retirement age of 59½ or older, or if you find yourself in need of money, you may need to make an early withdrawal from your retirement plan. An early withdrawal from your retirement plan is not without consequences – there will be taxes for sure, and quite possibly (likely?) penalties (referred to as “additional tax on early withdrawals” below). For  Rollover. A

Rollover. A  As reviewed in the article

As reviewed in the article  When a worker is receiving retirement benefits and/or members of his family are also receiving benefits based upon the retirement benefits, such as via spousal benefits, benefits for children, or other family members benefits, there is a maximum amount of benefit that can be distributed in total. (There is a separate maximum benefit computation for disability benefits, which we’ll cover in another article.)

When a worker is receiving retirement benefits and/or members of his family are also receiving benefits based upon the retirement benefits, such as via spousal benefits, benefits for children, or other family members benefits, there is a maximum amount of benefit that can be distributed in total. (There is a separate maximum benefit computation for disability benefits, which we’ll cover in another article.) The Full Retirement Age, or FRA (gotta love Social Security for their acronyms!), is a key figure for the individual who is planning to receive Social Security retirement benefits. Back in the olden days, when Social Security was first dreamed up, Full Retirement Age was always age 65.

The Full Retirement Age, or FRA (gotta love Social Security for their acronyms!), is a key figure for the individual who is planning to receive Social Security retirement benefits. Back in the olden days, when Social Security was first dreamed up, Full Retirement Age was always age 65.

When Congress was debating the merits of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) late last year, one of the items that took a lot of focus was the change to the Standard Deduction. The Standard Deduction was increased to nearly double what it was in years’ past. The deduction went from $12,700 in 2017 for joint filers to $24,000; for singles, the increase went from $6,350 to $12,000. Single filers over age 65 get an extra $1,600 deduction; married filers get to increase their Standard Deduction by $1,300 each if over age 65*. A byproduct of this change is that QCD (

When Congress was debating the merits of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) late last year, one of the items that took a lot of focus was the change to the Standard Deduction. The Standard Deduction was increased to nearly double what it was in years’ past. The deduction went from $12,700 in 2017 for joint filers to $24,000; for singles, the increase went from $6,350 to $12,000. Single filers over age 65 get an extra $1,600 deduction; married filers get to increase their Standard Deduction by $1,300 each if over age 65*. A byproduct of this change is that QCD ( In 2018, folks who are reaching that magical age of 66, which is Full Retirement Age (or FRA, in SSA parlance), may have some decisions to make. This is especially true for married couples, or folks who were married before and are now divorced. The restricted application still applies if you were born before 1954.

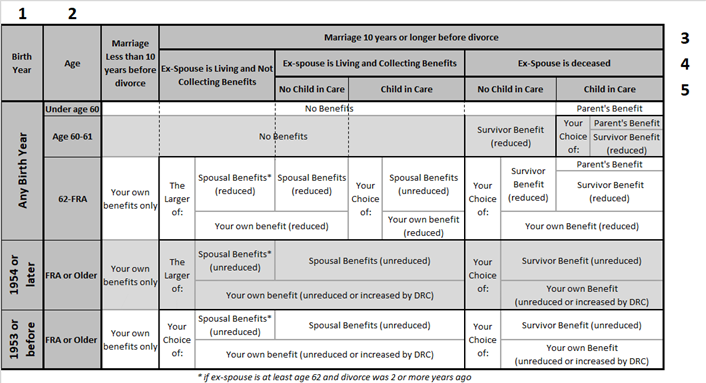

In 2018, folks who are reaching that magical age of 66, which is Full Retirement Age (or FRA, in SSA parlance), may have some decisions to make. This is especially true for married couples, or folks who were married before and are now divorced. The restricted application still applies if you were born before 1954.

It is important to know and understand who can be claimed as a dependent, as well as who can generate a personal exemption for your taxes. It’s not as simple as you might think, especially in complex family situations, such as when a child lives separate from one of his parents, or when there are more than two generations living in the same home.

It is important to know and understand who can be claimed as a dependent, as well as who can generate a personal exemption for your taxes. It’s not as simple as you might think, especially in complex family situations, such as when a child lives separate from one of his parents, or when there are more than two generations living in the same home. Under the newly-passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), there has been a slight change for folks who have taken loans from their workplace retirement plan and subsequently left the job before paying the loan back. These 401k loan distributions (as they are known) are immediately due upon leaving the job, considered a distribution from the plan if unable or unwilling to pay it back. This results in a taxable distribution, plus a 10% penalty unless you’re over age 59½. (You could avoid the 10% penalty as early as age 55 if you’re leaving the employer.)

Under the newly-passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), there has been a slight change for folks who have taken loans from their workplace retirement plan and subsequently left the job before paying the loan back. These 401k loan distributions (as they are known) are immediately due upon leaving the job, considered a distribution from the plan if unable or unwilling to pay it back. This results in a taxable distribution, plus a 10% penalty unless you’re over age 59½. (You could avoid the 10% penalty as early as age 55 if you’re leaving the employer.) Retirement can be one of the most anticipated and exciting times in a person’s life. When the time comes to start this new chapter, it is important to consider all of the factors to make the transition as easy as possible. Diligent financial planning is one of the most important things that can make a senior’s retirement successful, and it is especially helpful to know that there are some states that have better financial environments than others. Whether retirees already live in one of these states, or are looking for a new place to reside, knowing expense expectations can help seniors make the right decision about their future.

Retirement can be one of the most anticipated and exciting times in a person’s life. When the time comes to start this new chapter, it is important to consider all of the factors to make the transition as easy as possible. Diligent financial planning is one of the most important things that can make a senior’s retirement successful, and it is especially helpful to know that there are some states that have better financial environments than others. Whether retirees already live in one of these states, or are looking for a new place to reside, knowing expense expectations can help seniors make the right decision about their future. One of the provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) included the ability for an owner of a 529 education savings plan (such as Illinois’ Brightstart) to use the funds for K-12 private schooling just the same as for post high school expenses. This means that, at least at the federal level, owners of these plans will not pay tax on the growth of these funds if used for any private K-12 schooling. Previously this option was only available with a Coverdell savings plan, but TCJA extends this treatment to 529 plans.

One of the provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) included the ability for an owner of a 529 education savings plan (such as Illinois’ Brightstart) to use the funds for K-12 private schooling just the same as for post high school expenses. This means that, at least at the federal level, owners of these plans will not pay tax on the growth of these funds if used for any private K-12 schooling. Previously this option was only available with a Coverdell savings plan, but TCJA extends this treatment to 529 plans. For years now, the

For years now, the  With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, recharacterization of a Roth Conversion is no longer allowed. This begins with tax year 2018.

With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, recharacterization of a Roth Conversion is no longer allowed. This begins with tax year 2018.

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.