Photo credit: jb

When it comes to Social Security retirement benefits, many folks look at the payments as something they’ve earned… and that’s not totally off base if you happen to receive benefits, because the amount of the benefit that you receive is a direct result of your earnings over your career. But really, Social Security is something else altogether.

Technically, Social Security retirement benefits are referred to as “Old Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance”, or OASDI for short. I emphasized Insurance there, because that’s what it is. It’s not an investment, because there’s not an account with your name on a pile of money, just waiting for you to retire. Rather, this is an insurance program, specifically insurance against living longer than the average.

Like any other insurance plan, you pay in premiums (in the form of payroll taxation), and if you live to the appropriate age, you may receive a benefit from the plan. If you live longer than average, you might receive more in benefits than you ever paid in; on the other hand, if you don’t live long enough you might not receive any benefits from the plan, or very little benefits. In this case, your premiums go to paying for other insureds who do live longer. In addition, your spouse or child beneficiary(ies) may be eligible for benefits based on your record.

That’s how insurance works. Let’s draw a comparison to auto insurance. With auto insurance you pay monthly premiums to the insurance company, and if you have damage to your vehicle, or some other type of claim like damage to someone else’s property or medical expenses associated with an auto accident, then the insurance company pays for your damage, to a limited degree (after deductibles, and within plan limits).

Much the same as the description of Social Security, if you don’t experience an event and therefore don’t submit a claim, you won’t get any payments from the insurance company. Likewise, if all you ever had was a cracked windshield, you’d get much less payback than someone who totaled their car. Your premiums then are used to pay for folks who have experienced events and submitted claims for reimbursement.

No one goes into the agreement to purchase auto insurance with the express intent to get their money back out of the policy (well, at least no non-sociopaths).

So what are the similarities?

- You pay in premiums to both an auto policy and Social Security

- You pay these premiums to protect you against an event. In the case of auto insurance, it’s to help pay for damage to the car (among other things). Social Security protects you against living longer than you otherwise have money to cover.

- In both cases, the premiums of folks who don’t have claims (or fewer claims) are used to cover the claims of folks who experience the event being insured against.

With Social Security, assuming that you’ll live to the “average” (as determined by actuaries) age of around 82, you’ll receive a similar amount of retirement benefits no matter what age you start receiving those benefits. (There may be slight differences depending on the relative ages of a married couple but we won’t focus on that for now.) We might consider the amount received by about 82 to be the “base” amount of benefits.

But unless you have a reason to believe your lifespan will be something less than average, I’d guess that most folks are at least hoping to live some amount of time beyond the average. It’s that time beyond the average that makes the decision about the age to begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits so important. (Keep in mind that the lifespan of your spouse might be the important factor here as well, if your spouse is eligible for survivor benefits and outlives you.)

The relationship between the amount of Social Security retirement benefits and the age you file for those benefits is that, the longer you delay (between the earliest filing age of 62 and the latest age of 70) the larger the monthly benefit you will receive. And subsequently, if you live past the average age mentioned above, each month of delay results in a larger lifetime benefit, maximized if you delay to the latest filing age of 70.

Usually, delaying filing for Social Security benefits to age 70 requires a trade off somewhere – maybe you’ll have to take more money out of your IRAs or other retirement savings earlier than you’d expected, or you might need to work longer than planned. Either of these options can bridge the gap between the earliest filing age and the latest filing age in order to help you maximize your Social Security benefit.

Since Social Security retirement benefits are tax efficient, cost-of-living-adjusted, guaranteed (don’t sacrifice me on the guaranteed part, we’re not talking about policy here), and infinite (once you start receiving the benefit you’ll receive it for life), it makes a great deal of sense to maximize that monthly benefit amount. Especially so if you plan to live past “average”.

Think about it – above we mentioned a “base” amount of money you’ll receive from Social Security benefits by the average age of death, around 82 years of age. So if you’re average, you’ll get the base amount of money, and that’s all. If, unfortunately, you don’t live as long as the average, you won’t get as much in benefits – that’s the way it works, some folks don’t win the lottery of life.

But if you live longer than the average age, every single month’s benefit is a bonus above the base. So again I ask, if you are expecting to live longer than the average, why wouldn’t you try to maximize the amounts that will be, essentially, your bonus?

For a minimized example, let’s say other than your Social Security benefits you have IRA funds and other sources that just make up the difference between your living expense needs and the amount you’ll receive in Social Security benefits. When you get to age 83, you’ve expended all of your other sources completely, and now all you have is Social Security to live on – doesn’t it make sense that you should have maximized this benefit, so that as your life expectancy goes onward you’ll have the largest possible monthly benefit?

I should point out that in a case like the above minimized example, you should probably take some other action earlier, like working longer, or finding ways to reduce your living expenses. Otherwise when you outlive your savings you may be faced with some difficult decisions and be forced to take on a spartan lifestyle by comparison.

Arguments against delaying:

- I don’t have enough money saved otherwise to get me through to the later filing age.

- Not much to counterpoint this with. If you don’t have the resources to delay, you may have no choice but to either file for Social Security earlier, or continue working (or pick up a part-time job) in order to cover your living expenses. Another viable alternative is to reduce expenses somehow – downsizing your home, lifestyle, etc., or selling some of your “things”.

- I don’t want to use my savings so early in my life! I’ve saved all these years, using it to delay filing only draws down how much money I’ll have for later on. (Also – I want to leave something from my retirement account for my heirs!)

- (building off the prior answer) If you have at least enough funds to get you through to the later filing age, you should use those less attractive funds (fully taxable, not guaranteed, not cost-of-living-adjusted, and finite – there’s only so much in the pot) to allow yourself to maximize your Social Security benefits. Face it, if you’re that close to the edge with your savings, you need Social Security benefits to be as large as possible.

- Besides, you saved that money for a reason – to help pay for your retirement. That’s exactly what you’ll be doing as you use these funds to live on while delaying Social Security filing.

- Regarding leaving something to your heirs, if it comes down to paying for food versus leaving that inheritance behind, you know what the choice is going to be. If you live longer than your money can last, the heirs will be the last thing on your mind.

- I can do so much better with my own investing than Social Security can. I’ll take the benefits early and invest them to maximize my possible income stream for later in life.

- First of all, delaying results in an increase to your monthly benefit amount by anywhere from 6%-8% for each year of delay, guaranteed. (That guarantee should have no arguments). If you can guarantee a return of 6%-8% every year, you’re a genius and you have no business reading such mundane articles as this. Go solve world hunger, why don’t you?

- Secondly, unless you’re extremely well disciplined, this concept of “I’ll invest it all” is sham and you’re likely fooling yourself. Very few people could put this into action, and then you’ve still got the guaranteed 6%-8% factor mentioned above to overcome.

- Actually, in the long run, that 6%-8% increase works out to much more, due to the fact that as long as you live you’ll continue receiving your Social Security benefit. Think about how that can play out if you live to 90, 95, 100, or 110!

- What if I don’t live to age 82 (or age 70)? Then all of that money is just wasted. My uncle (or cousin, brother, neighbor, etc.) worked his whole life paying into Social Security and died at age 61½ (or 69, etc.) and got nothing.

- Just the same as with auto insurance, in some cases you pay into it for a long time and never make a claim. In other cases you have (heaven forbid) a terrible auto accident and have huge medical, property, and auto replacement claims, which are paid by your auto insurance. With Social Security retirement benefits, there’s always the possibility that you might not get any benefit, or very little in the way of benefits over your lifetime if your life is shortened by an untimely death. It’s the gamble that you take, to ensure that you’re covered in the event of living longer than expected.

- I’m filing as early as possible to get my money back.

- Keeping with our comparison to auto insurance, often there are small possible claims that you could submit, like a door ding from a parking lot. Auto insurance has disincentives to discourage these small claims – submitting and being paid for these small claims will result in an increase to your premiums. Social Security’s disincentives apply when filing earlier in your life – you’ll receive a smaller monthly benefit amount when filing sometime before the maximum age.

- Social Security is going broke. I’m filing now (or as soon as possible) while it’s still available.

- Suffice it to say – if you feel this way, then by all means, go ahead and file whenever you want to. I disagree with your viewpoint, but I will not argue it, experience tells me that this point of view is not likely to be changed so I won’t try.

We didn’t cover the nuances involved with spousal benefits, dependent benefits, or survivor benefits. These auxiliary benefits could impact your filing decision in either direction, and coordination of all available benefits is necessary to achieve an optimal outcome.

I get a lot of questions about when to take Social Security benefits most efficiently, and when to begin Spousal Benefits. And unfortunately, I am often at a loss for giving a specific answer to the individual, because I just don’t have enough information.

I get a lot of questions about when to take Social Security benefits most efficiently, and when to begin Spousal Benefits. And unfortunately, I am often at a loss for giving a specific answer to the individual, because I just don’t have enough information.

You may or may not be familiar with the concept of Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) as it relates to company stock owned in your 401(k) plan. Click the link to get a rundown on it if you’re not familiar with

You may or may not be familiar with the concept of Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) as it relates to company stock owned in your 401(k) plan. Click the link to get a rundown on it if you’re not familiar with  Since the housing market downturn, the national pastime of “property flipping” has fallen in popularity – heck, I haven’t seen a TV show on property flipping in ages. But the activity of buying a fixer-upper, applying a little sweat equity, and then reselling for a profit has been going on ever since Gog first rehabbed and sold that condo-cave with a view.

Since the housing market downturn, the national pastime of “property flipping” has fallen in popularity – heck, I haven’t seen a TV show on property flipping in ages. But the activity of buying a fixer-upper, applying a little sweat equity, and then reselling for a profit has been going on ever since Gog first rehabbed and sold that condo-cave with a view. I was recently re-reading an older book, The Money Game, by “Adam Smith”, and I came across a very poignant passage that I thought I should share. This book was written in 1967, and it is a very interesting take on money and how we view it.

I was recently re-reading an older book, The Money Game, by “Adam Smith”, and I came across a very poignant passage that I thought I should share. This book was written in 1967, and it is a very interesting take on money and how we view it.

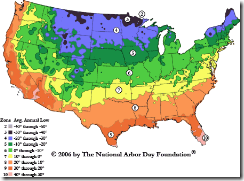

We’ve covered a lot of ground with regard to how various tax laws impact your retirement plans: pensions, IRAs, 403(b) and 401(k) plans. But we’ve primarily focused on the US income tax laws (the IRS) affect your plans – and there are many nuances that you need to take into account with regard to state tax laws.

We’ve covered a lot of ground with regard to how various tax laws impact your retirement plans: pensions, IRAs, 403(b) and 401(k) plans. But we’ve primarily focused on the US income tax laws (the IRS) affect your plans – and there are many nuances that you need to take into account with regard to state tax laws.

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.