Photo credit: jb

Many of the Social Security rule changes that have been put into place in the past several years have removed flexibility in Social Security claiming strategies. However, Survivor Benefits, coordinated with your own retirement benefit (if you’re a surviving spouse or surviving divorced spouse), remain as one of the last bastions of flexibility for claiming strategies.

Survivor benefit first, retirement benefit later

As we’ve discussed in other articles, claiming Survivor benefits early and then claiming your own Retirement benefit later provides one flexible claiming strategy that you might be able to employ.

For example, Dina is divorced (after more than 10 years), unmarried, age 60, and her ex-husband passed away recently. Dina could file for and receive a Survivor benefit based on her late ex-husband’s record right away, and collect that benefit for a while. Then, at any point she could switch over to her own retirement benefit if it is larger than the Survivor benefit, and continue collecting that benefit.

This strategy works well if the surviving spouse has earned his or her own retirement benefit during his or her career, and at some point the retirement benefit will grow to a point when it’s greater than the Survivor benefit. This crossover might occur within a few months after she starts taking the Survivor benefit, or at any point along the spectrum between start of Survivor benefits and his or her age 70.

In Dina’s case, her own retirement benefit will be greater than the Survivor benefit at once when she reaches age 62. (Keep in mind, if she’s started the Survivor benefit at age 60 this benefit will be reduced; likewise if she starts her own benefit at age 62 the retirement benefit will also be reduced.) Dina could start receiving the larger retirement benefit at age 62, or at any point through the years up to age 70 if she wants.

When Dina starts receiving the retirement benefit, since the retirement benefit is larger than the Survivor benefit, the Survivor benefit will end. Technically (and this is important to the rules) the Survivor benefit will terminate if Dina’s PIA is larger than the PIA upon which her Survivor benefit is calculated. It’s a technicality, because generally if Dina’s reduced retirement benefit is greater than the reduced Survivor benefit, more than likely the PIA of each benefit will correspond in size.

At any rate, that’s how the “Survivor benefit first, retirement benefit later” strategy works. The key to this strategy is that starting the Survivor benefit early has no impact on Dina’s later ability to file for and receive a retirement benefit. The delayed receipt of the retirement benefit is added to Dina’s record as if she had not filed for a previous benefit (in other words, no deeming is applied).

Retirement benefit first, Survivor benefit later

This strategy can work in the reverse as well. Dina could wait until her age 62 and start receiving her own retirement benefit, reduced due to the early filing. Then she could wait until as late as her Full Retirement Age (for survivor benefits, slightly different from the regular FRA) and file for the Survivor benefit. This filing would be unaffected by the early filing for her retirement benefit.

Survivor benefit first, then retirement benefit, then Survivor benefit again

You might think that this is where the flexibility story ends, but you’d be wrong. There is one other strategy that the rules allow. In Dina’s case, she could start taking the Survivor benefit at age 60 (reduced to the minimum), and then at or after age 62 (but before her Survivor benefit FRA) file for her own retirement benefit. If, upon filing for her retirement benefit the retirement PIA is greater than the Survivor benefit PIA, the Survivor benefit will terminate at this point, as discussed earlier.

Now is when this final flexibility option comes into play. If it turns out that Dina’s Survivor benefit might at some point become larger than her Retirement benefit, she has the option to re-entitle the Survivor benefit. (Reentitlement is SSA’s term for filing for and receiving a benefit that had been received previously, but had terminated.)

The numbers have to work out in her favor, but follow this: starting her Survivor benefit at age 60 resulted in a reduction of the maximum amount, 28.5%, to Dina’s Survivor benefit. This is based on her Full Retirement Age of 67, which means a reduction period of 84 months (7 years).

But if she starts her own retirement benefit at age 62, thus terminating the Survivor benefit, she has the option to re-entitle the Survivor benefit, with the calculation eliminating those months during which she was receiving the retirement benefit (and the Survivor benefit was terminated). So if she waits until her FRA for Survivor benefits, her newly re-entitled Survivor benefit would be calculated based on a reduction of only 24 months – those months that she had collected earlier. Full Retirement Age is the latest that it makes sense to apply this re-entitlement, as beyond FRA the Survivor benefit will not increase except for annual COLAs. (For the rules geeks in the audience, see POMS RS 00615.301A.2, second bullet point for the explanation and another example.)

So instead of an 84 month reduction of 28.5%, Dina’s new Survivor benefit would only be reduced by 24 months, which calculates to a reduction of 8.14%. If, for example, her original reduced Survivor benefit was $1,000, this adjustment upon re-entitlement would bring the benefit up to $1,285, plus the COLAs from the intervening years.

Not a lot of surviving spouses and ex-spouses will have this flexibility available to them, but for the ones that do have it, this strategy can help out quite a lot, I imagine.

The strategy outlined above only applies in a situation where the Survivor benefit that is re-entitled is the same Survivor benefit that had been previously received. Otherwise, if a new Survivor benefit (based on the record a different spouse, also deceased) is applied for, it will be treated as the first time you’ve filed for a Survivor benefit. The prior reduced Survivor benefit has no bearing on the amount of this new Survivor benefit.

This one doesn’t work in vice versa

It’s critical to note that the above strategy (Survivor benefit first, then retirement benefit, then Survivor benefit again) does not work in the reverse. Dina could not, for example, begin her retirement benefit at age 62, then switch to Survivor benefits at (for example) 64, and then switch back to retirement benefits later on. This is because of the technical matter that I mentioned above, where the Survivor benefit becomes terminated upon receipt of a higher retirement benefit. The retirement benefit does not similarly terminate when a higher Survivor benefit starts up. In that case, the Survivor benefit (if higher than the retirement benefit) becomes an “excess” benefit, and the difference between the retirement benefit to the Survivor benefit is simply added to the retirement benefit.

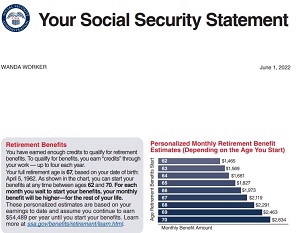

Back in the olden days, we all received an annual statement from the Social Security Administration detailing your benefits projected to your potential retirement age(s). Nowadays you can go online (

Back in the olden days, we all received an annual statement from the Social Security Administration detailing your benefits projected to your potential retirement age(s). Nowadays you can go online (

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.