Chances are you’ve seen an advertisement or some sort of article talking about how Social Security benefits will be changing in 2021. Usually these articles have a very dramatic headline, such as “After 2021, you’ll never be able to get as much benefits from Social Security! Act Now!” – followed by information to attend a seminar or contact a firm to help you out.

I understand a lot of folks are concerned about this, but I believe it’s misguided concern brought about by sensationalists who have something to sell. The truth is that the much ballyhoo’d changes in 2021 have been in place since 1983, and nothing you can do will avoid the application of these rules.

The Rule Change

In 1983, Congress made changes to the way Social Security works, in order to increase the probability of the system maintaining solvency. This was brought about by the crisis situation that was occurring in 1982, which was the last time Social Security’s trust fund was in danger of running short of money (as has been projected to occur 2035, per the 2019 Social Security Trust Fund Report).

At that time, the Full Retirement Age (FRA) for Social Security beneficiaries was 65. This had been the FRA since the inception of the system, and had been in place for approximately 50 years at that point. In order to help the system out, FRA was gradually increased over time.

It started with folks who were born in 1938 – who were 45 years old in 1983. FRA increased by 2 months for these folks, and increased by another two months for the following birth years up to the birth years of 1943 thru 1954. The FRA for these folks was set at 66 years. Beginning with birth year 1955, FRA is increased again by 2 months. For each subsequent birth year after that, FRA is increased by another 2 months, until it reaches 67 for folks born in 1960 or later.

In 2021, the first people born in 1955 will be reaching their FRA – which for the first time in 11 years has increased. These people reach FRA at age 66 years and 2 months. But this isn’t new! These rules have been in place since 1983.

No rules are changing in 2021. There are different factors being applied for folks who reach FRA in 2021 and thereafter, but the rules have been in place since 1983.

The Rules

Here’s how the rules apply – for everyone: For all birth years after 1943, the Delayed Retirement Credit is 2/3% per month, which works out to 8% per full year of delay. The reduction calculation for starting benefits before your FRA is also the same for all – 20% (5/9% per month) for the three full years (36 months) closest to your FRA, and 5% per year (5/12% per month) for any months more than 36 before your FRA.

First, a quick definition: PIA – Primary Insurance Amount – This is the unreduced (and not increased) benefit that you will receive if you file at your Full Retirement Age.

Let’s look at each year of birth in order. Here are the factors used to calculate your benefits:

Birth year 1943-1954

– FRA is age 66

– minimum benefit is 75% of your PIA (48 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 132% of your PIA (48 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1955

– FRA is age 66 years, 2 months

– minimum benefit is 74.17% of PIA (50 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 130.67% of PIA (46 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1956

– FRA is age 66 & 4 months

– minimum benefit is 73.33% of PIA (52 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 129.33% of PIA (44 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1957

– FRA is age 66 & 6 months

– minimum benefit is 72.5% of PIA (54 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 128% of PIA (42 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1958

– FRA is age 66 & 8 months

– minimum benefit is 71.67% of PIA (56 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 126.67% of PIA (40 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1959

– FRA is age 66 & 10 months

– minimum benefit is 70.83% of PIA (58 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 125.33% of PIA (38 months of delay increase)

Birth year 1960 and thereafter

– FRA is age 67

– minimum benefit is 70% of PIA (60 months of reduction)

– maximum benefit is 124% of PIA (36 months of delay increase)

Practical Application of the Rules for YOUR Situation

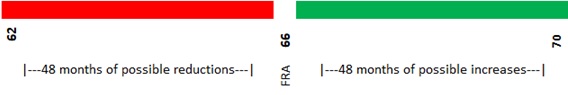

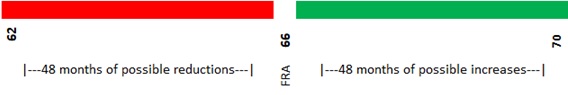

Perhaps it might help to visualize a timeline of the 96 months between age 62 and age 70. For folks born between 1943 and 1954, the FRA point is at age 66. At that point, there are 48 months to the left of FRA (maximum number of months before FRA that you can file, therefore 48 months worth of reductions can be applied). On the right of FRA, there are 48 months before age 70, so that there are a maximum of 48 months’ worth of increases by delaying. See below:

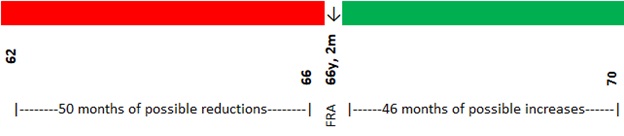

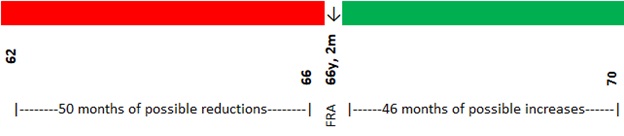

However, for someone born in 1955, the FRA point is at 66 years and two months. This leaves 50 months to the left, and 46 months to the right. So the decreases are greater at the minimum filing age, and the increases are less at the maximum filing age. See below:

However, for someone born in 1955, the FRA point is at 66 years and two months. This leaves 50 months to the left, and 46 months to the right. So the decreases are greater at the minimum filing age, and the increases are less at the maximum filing age. See below:

Since increases and decreases are based on how many months before or after FRA that you file, when there are more months to the left the maximum decrease will be greater. Likewise when there are fewer months to the right the increases will (at maximum) be less.

Since increases and decreases are based on how many months before or after FRA that you file, when there are more months to the left the maximum decrease will be greater. Likewise when there are fewer months to the right the increases will (at maximum) be less.

To calculate the minimum benefit for 1955 birth year, as indicated above there are 50 months of possible reductions. The closest 36 months determine a 20% decrease, and the remaining 14 months (at 5/12% per month) determine an additional 5.83% decrease, multiplying 14 by 5/12%. Adding these two together we come up with 25.83%, so the minimum benefit is 74.17% for birth year 1955.

Calculating the maximum benefit amount for 1955 birth year is more straightforward – every month of delay produces a 2/3% increase. Multiplying 2/3% by the 46 possible months of increase results in a total maximum increase of 30.67% for birth year 1955.

Nothing is Changing in 2021

If you’re reaching FRA in 2021, these factors have applied to every calculation done to project your benefits. NOTHING CHANGES AS OF 2021, it’s already in place (since 1983), determined by your year of birth. So again I say, the year 2021 should have no impact on your filing decisions.

In fact, if you’re reaching FRA in 2021, these factors began applying to your situation in 2017, when you reached age 62. If you calculated the minimum benefit for starting at age 62, you’d have found that the benefit amount was 74.17% of your PIA – not 75%, which was the case for folks born the year before. The same applies to anyone born in or after 1955 – the minimums have been in place all along (since 1983).

Hope this clears up any misconceptions that may have arisen from the drama that is being promoted as if it were a crisis.

(jb note: Astute reader JH pointed out an error in the calculation below, which I’ve corrected. The end result of the taxation increase is the same, but there was a problem in the calculated taxable income in the previous version.)

(jb note: Astute reader JH pointed out an error in the calculation below, which I’ve corrected. The end result of the taxation increase is the same, but there was a problem in the calculated taxable income in the previous version.)

With due regards to Natalie Choate for initially putting together this list, below are the currently-legal methods for funding a Roth IRA account:

With due regards to Natalie Choate for initially putting together this list, below are the currently-legal methods for funding a Roth IRA account:

I’ve had a few questions about this topic over the years, so I thought I’d run through a few examples and explain it.

I’ve had a few questions about this topic over the years, so I thought I’d run through a few examples and explain it.

However, for someone born in 1955, the FRA point is at 66 years and two months. This leaves 50 months to the left, and 46 months to the right. So the decreases are greater at the minimum filing age, and the increases are less at the maximum filing age. See below:

However, for someone born in 1955, the FRA point is at 66 years and two months. This leaves 50 months to the left, and 46 months to the right. So the decreases are greater at the minimum filing age, and the increases are less at the maximum filing age. See below: Since increases and decreases are based on how many months before or after FRA that you file, when there are more months to the left the maximum decrease will be greater. Likewise when there are fewer months to the right the increases will (at maximum) be less.

Since increases and decreases are based on how many months before or after FRA that you file, when there are more months to the left the maximum decrease will be greater. Likewise when there are fewer months to the right the increases will (at maximum) be less.

Long-Term (7 to 10 years)

Long-Term (7 to 10 years) Close At Hand (Reference file)

Close At Hand (Reference file)

As you are probably aware, each year your Social Security benefits can be increased by a factor that helps to keep up with the rate of inflation – so that your benefit’s purchasing power doesn’t decrease over time. These are called Cost Of Living Adjustments, COLAs for short. The increase for 2019 was 2.8% – and for 2020 the COLA is 1.6%. But how are those adjustments to your benefits calculated?

As you are probably aware, each year your Social Security benefits can be increased by a factor that helps to keep up with the rate of inflation – so that your benefit’s purchasing power doesn’t decrease over time. These are called Cost Of Living Adjustments, COLAs for short. The increase for 2019 was 2.8% – and for 2020 the COLA is 1.6%. But how are those adjustments to your benefits calculated?

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC®

Sterling Raskie, MSFS, CFP®, ChFC® The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on

The latest in our Owner’s Manual series, A 401(k) Owner’s Manual, was published in January 2020 and is available on  A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on

A Medicare Owner’s Manual, is updated with 2020 facts and figures. This manual is available on  Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at

Social Security for the Suddenly Single can be found on Amazon at  Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be

Sterling’s first book, Lose Weight Save Money, can be  An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the

An IRA Owner’s Manual, 2nd Edition is available for purchase on Amazon. Click the link to choose the  Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the

Jim’s book – A Social Security Owner’s Manual, is now available on Amazon. Click this link for the  And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.

And if you’ve come here to learn about queuing waterfowl, I apologize for the confusion. You may want to discuss your question with Lester, my loyal watchduck and self-proclaimed “advisor’s advisor”.